The following interview is a montage of conversations that took place between Chinese sound artist Yan Jun [YJ] and researcher Adel Wang Jing [AW] between July 2010 and October 2011 in Beijing. Translation from Chinese to English by Adel Wang Jing…

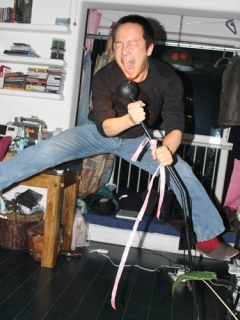

Yan Jun [B, Lanzhou 1973] is an artist based in Beijing working with sound and language. As an improviser he utilises feedback, space and audience movement often employing objects such as sun flower seeds as instruments for composition. He is the Founder of Sub Jam/Kwanyin Records, member of FEN [Fareast Network] and has toured internationally and throughout China. During 2011 he participated in the Asian Culture Council residency in New York and the Rotterdam International Poetry Festival. Jun recently received an Prix Ars Electronica Honorary Mention for his work Music for Listening on the Earth and is currently producing his latest work, Living Room Tour. For comprehensive information please visit http://www.yanjun.org/

………………

YJ: …To talk about sound art, it is necessary to understand that the term sound art means different things in different languages: audio art, sound art, klangkunst… this is a new term, and it has different meanings in different languages. Artists in different countries are doing different things with sounds.

AW: What about China?

YJ: In China, we do not have our own term for sound art yet. I guess something like “声艺,” or… anyway, we don’t have our own term, what we are using now is a literal translation of the English term sound art. When we use this translation we are often limited in talking about what the English speakers have already been discussing. There is no sound art in China now.

AW: By now, do you mean currently?

YJ: Yes, currently. But it is not quite right to say there is, or there is not. The reason why there is no such a term in China is that you could not find appropriate Chinese characters corresponding to the two English words. So we could only translate it literally. It is a new term in Chinese, and it gives everyone a chance to introduce foreign cultures and foreign arts. It provides a foreign context when you use the term. And then you suddenly have this so-called internationalism. At the same time, some musicians and artists are doing things similar to what sound artists are doing in the Western context. That is, some are actually making sound art works very similar to works by sound artists in the West, but they [Chinese musicians] still think they were making music or are just playing. In a Chinese context, we are using the translated term of sound art because we do not have other choices yet. The fact is that there will be more and more sound art works, because of internationality. Imitation and replication is an unavoidable trend. People always want to be who they are not. However, historically speaking, Chinese pigeon whistles, sound design in traditional landscape architecture, and Japanese Suikinkutsu should not be included in the category of “sound art.” What I want to say is that sound art only belongs to the existing western framework: to join the battlefield of modernity.

AW: What term would you use for yourself and your work?

AW: What term would you use for yourself and your work?

YJ: It depends. Sometimes I use “experimental sound,” sometimes “experimental music,” “sound art” or “sound.” I use different terms in different contexts. Another thing that is unique in China is when we say someone is making sound art; it is most likely that this person does not have sound art works. Most of their works are music. Maybe we could ask, isn’t it true that after John Cage, anything related to listening becomes music? In my opinion, if there has to be a rubric that could be used to distinguish music from sound art, sound art requires a certain kind of thinking or conceptualization. So in the context of China, maybe one difference between the two [music and sound art] is that music does not require too much thinking; it is more instinctual. Sound art is closer to contemporary art in terms of thinking. This is because in China the body is still a crucial element of resistance, fighting against systematization and the increasingly rationalized neo-capitalism. People [Chinese musicians] do not like to think. Instead, they use their instinct and their bodies, which seems to make sonic works with any kind of conceptualization or thinking sound art.

AW: It seems that you are suggesting sound art is conceptual art.

YJ: In fact, in Western Europe and the U.S., sound art is more technological or multi-media. I think this is a failure. For me, everything that makes or has sound could potentially be sound art, and it depends on how I listen to it. Popular music could be materials of sound art, depending on how I listen to it and how I make other people listen to it. When I use popular music as the sources of my creation, it becomes part of sound art. So beside sounds, there is something else that makes it sound art. I think it’s important to ask the question that in China except for performing live on stage and releasing CDs, who are making other kinds of sound art works?

AW: What about sound works in the nature of Fluxus or Happenings?

YJ: It depends on where the focus of investigation and thinking is. If you are thinking about communication, challenging the relation between the public and the public space, and disturbing a certain social order, and if sound is only a means for you, then it is not sound art.

AW: How important is it to make such distinctions?

YJ: It is not important at all. But during the process of making distinctions, I have done research, and have thought about and understood many other things.

AW: You mentioned your dispute with Zhang Jian [a member of FM3] during a music festival with me before. FM3’s Buddha Machine is almost a representative work for China’s sonic scene. Probably that’s also what most people in the West know about if they talk about sound art in China. Could you tell me more about your disagreement with Jian.

YJ: We started to argue about music three years ago. After someone’s performance, I commented that the music was too full, and I didn’t like it. But Zhang Jian thought the opposite and argued with me. For him, a good piece of music should be complete and full. It should have an introduction, transitions, development, climax and an ending. There is always a perfect structure. But this is not his point. His point is that good music should be pleasant for the ear and enjoyable. In my opinion, it is a typical attitude folk musicians hold. They have to make sure that their music is entertaining and the audiences like the music and pay for it. Instead, calligraphy is an example to support my point. No one considers regular script as art. Regular script is for practicing and healing like an official poster. The best calligraphies are always those imperfect ones, those that break the rules. It occurs during the uncontrollable moment when great calligraphers improvise. I disagree with Zhang Jian on what music should be. The difference exists in how and why one makes music.

AW: In your opinion, is Zhang Jian a sound artist then?

YJ: I call the group FM3 sound artists when they made the Buddha Machine. Christiaan Virant has made sound for Ding Yi’s exhibition. During that time he also made something conceptual, such as Zenhead. They have tried to make more art-oriented works, but after a while they realized that they did not like this kind of work. They like music more. I guess they consider making art too demanding; there’s too much thinking involved. Zhang Jian hates the term sound art; he thinks it is too hypocritical. For many handicraftsmen, they do not like to think too much. When you talk about noise or sound art with a folk musician, he will not like it. He will not like it especially when noise or sound art gains this high-art status in the society. I think this is a kind of plain and simple proletariat sensibility. Recently someone translated Alain Badiou’s Fifteen Thesis on How Can Contemporary Art Avoid Being Formalist Romantic? [当代艺术的十五个论题:怎样不做一个浪漫主义者]. I found much of what he says clicks with my own thoughts. What I want to do with sound is not to entertain or comfort, but to liberate. The most important thing in contemporary art is the liberation of human beings. Wang Fan* once said, many people have not lived yet.

AW: So what is sound art for you? Or what does it do for you?

YJ: My music should never comfort or entertain people. When it does these things, its real value and mission will be neglected. My sounds do not propagate, and they do not make use of listeners or comfort them. This is not a statement of my wish. It is what I think and what I am doing with my music. Over these years of practices and performances, I gradually realize that sounds I really enjoy in my work are often piercing, full of ambiguity, and make listeners and myself uncomfortable. I do not feel moved or excited when I make sounds that are sweet. Instead, I feel moved when hearing sounds that make me feel alone, and those that make me listen by myself with myself, insulated from other things. This is my favorite sound. My listeners are those who are alone, or those become alone through my sounds, at least at the moment.

AW: Is this asking a lot from your audience both intellectually and sensually?

AW: Is this asking a lot from your audience both intellectually and sensually?

YJ: I don’t think so. This is only a temporary transformation. You enter the state of aloneness through listening. Aloneness does not solve any problem immediately. It is only to make you exist by yourself. Many musicians like to say that their music is to help the listeners forget their loneliness. It is a shame, a drug. It is drinking poison to quench thirst**. It is an illusion that we create to comfort ourselves. But my logic is that we exist in the world alone. We have to make efforts to admit and face this fact. Only after its acceptance, we could be with other people who are also alone. We should not hide or pretend to forget this fact by hanging out with friends, eating, drinking together, or getting married. I am not against having parties and staying with friends. But after the parties, you go back home by yourself. Even if you go back with your partner, before falling asleep, there is a moment of absolute aloneness. For many people, this moment is too short to be noticed. But I must enlarge this moment, and make it longer, because only in this moment do I clearly feel and understand my existence. This moment, for me, is individual liberation. [Long pause]…Aloneness is always good. It is not loneliness, not lacking. Aloneness means you are yourself, you do not lack anything. Aloneness is wholeness.

AW: Recently, you did a three-month-long concert series called living room tour starting in July [2011] in Beijing. It was a refreshing way of producing a concert in that you go to make sounds in people’s apartments upon their invitation. I guess by changing from public spaces like music clubs or galleries to private ones of people’s apartments, it secures a better listening environment, but at the same time, it brings a big challenge to the musicians since you don’t really know what kind of tools you are going to have or what kind of audience or space you will face. Would you tell me how this idea started, or in other words, what is the motivation?

YJ: The motivation is to first create a listening and performance space for myself. The kind of sound I like is difficult to make in China, because either the sound system is very bad, or audience members drink and chat when I perform. Secondly, it is a personal desire. I am always curious in people’s ways of living, their everyday life. I have the desire to enter the other’s personal and private spaces. Thirdly, the living room concert is also about faith: if you believe that a Mandala [a world] has no difference in scale, then you should create it in any place. Living room concert is about creating a stage, a space suitable for performance, it is also to create a listening event, a world. Faith is about practice. This project [the living room concert] is a small but powerful engine. It will ignite huge energy. Changing the world is not symbolic; it is what is actually happening. When we speak of creating reality or something real, in my opinion, doing living room concert is much more significant than taking part in any political movement.

AW: Would you say something about the kind of openness you allow for this living room concert?

YJ: The openness of living room tour is that any one can invite me, but he/she has to pay for it. This is not capitalist democracy. I ask for equal relations. I am not an entertainer, neither am I an idol. I have to ignite and give life to an event together with the audience. So I have to do a lot of preparation, to activate the audience.

AW: Now you finished the tour, would you say anything about it? Was it satisfying and what did you get from it?

AW: Now you finished the tour, would you say anything about it? Was it satisfying and what did you get from it?

YJ: I plan to continue this project. Next year, I will start doing it in Shanghai. If I have opportunities to live in other cities for a while, I will do it there. This will be my date with people. The concert tour is not about private space as opposed to public space in general, but private spaces of audience members. It is not the kind of event that requires a big house, friends and acquaintances in the art circles to happen. Instead, as long as you have a place to sleep, you could create a world together with me. In Comparison to using a professional performance space, I find that a space like this is much closer to natural everyday life. It is common and magical. I guess this is an ideal state of “revolutionary commonality.” To liberate the event of sound and the event of listening from the socialized division of labor, to let it occur where it should occur the most. This is exciting for me.

FIN

Download printable English version [here]

Download printable Chinese text version [here]

Footnotes:

*Wang Fan is a Chinese experimental musician and sound artist. He is identified as the first experimental musician in Mainland China with his lo-fi music work Dharma’s Crossing released in 1996.

**A Chinese saying: 饮鸩止渴

………………

Adel Wang Jing is a Ph.D candidate in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts in Ohio University. An ethnographer, a writer, and a listener. Her disseration is on China’s sound art and experimental music practices in relation to concepts of freedom and affect. Trained in performance studies and aesthetics, she engages concepts and affects on both philosophical and everyday levels. Her ongoing writing project is on sound, listening and improvisation.

Pingback: 芥末日记 V.7» Blog Archive » 姨太太老九尖声叫着

Good morning…I have just awaken this am and will reply asap.

Welcome Yan and Adel, and h e a r is to your ongoing contributions to Global sounding vocabularies.

really nice to see the videos of chinese soundartist.im amazed…i am a soundartist also in the philippines and want to collaborate with you guys in the near future

Hello Adel Wang, Jing/Yan Jun and friends.

Please lend your ears to this stream ’til May 13

From Belgium

http://www.festivalkortrijk.be/en-gb/f-program/26/windribbon-insect-recording-studio

the right URL is

http://icecast01.v2.nl:8000/windribbon.m3u

open the link on your desktop, a small file with the name windribbon.m3u downsloads on your desktop, double-click this file, VLC (download free) or some other program should then play it for you after some seconds

Sincerely leif BRUSH Duluth Minnesota US

http://rhizome.org/commissions/proposal/2588/

Pingback: Artist Turns Living Rooms Into Immersive Listening Experiences - PSFK

Pingback: Interview with Yan Jun_Ear Room Guest Edition | Sonorous Presence